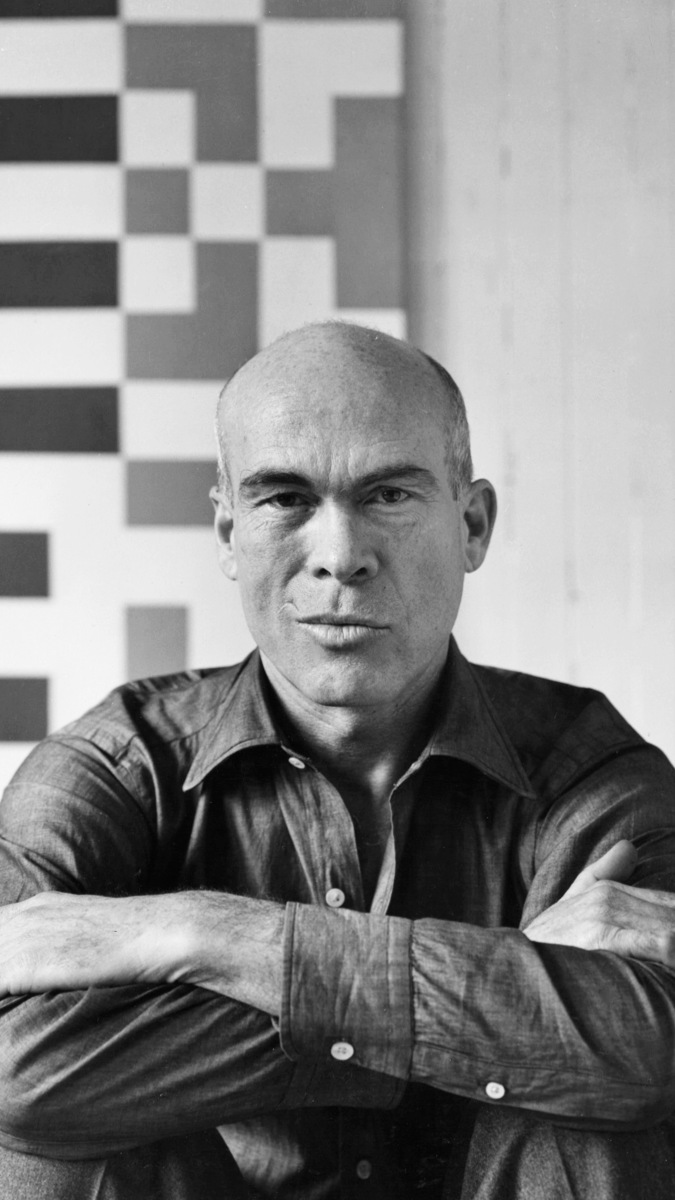

photo by Gene Pyle

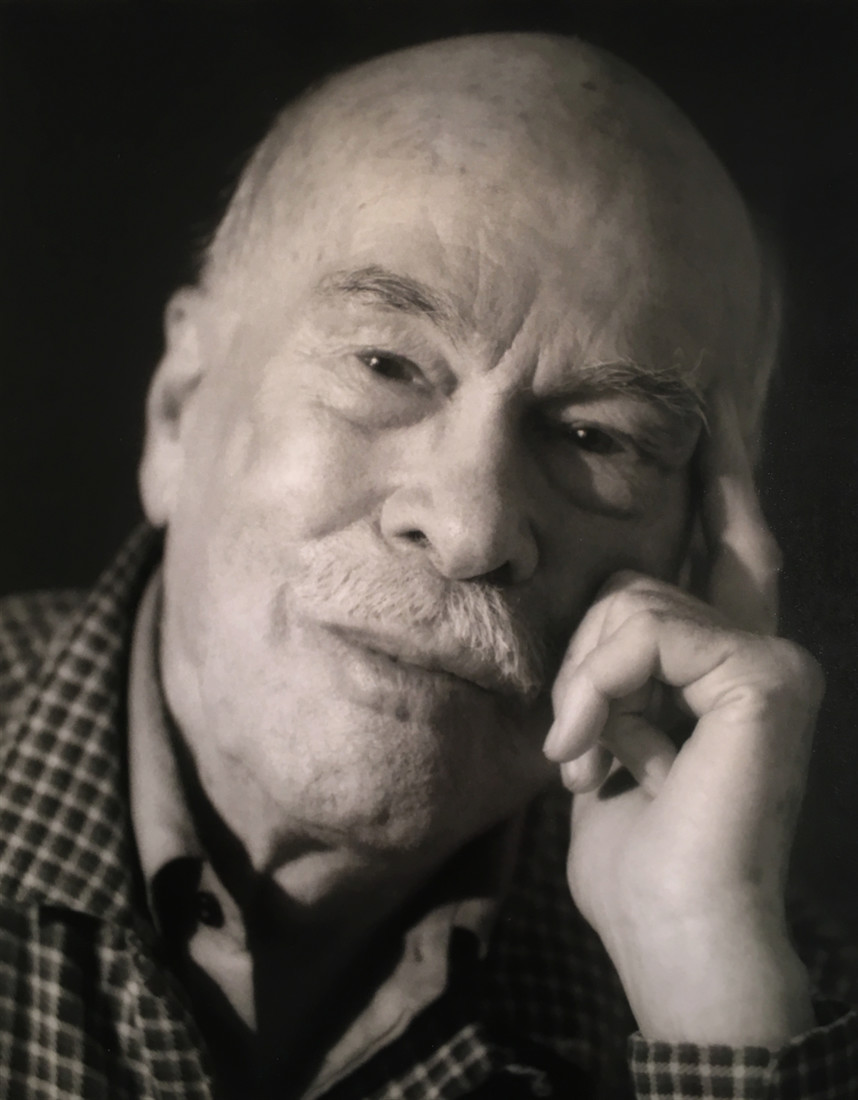

Anyone who knew Leon Polk Smith well was struck time and again by his force of character. As Robert Mead Jamieson, Smith’s assistant and companion of more than four decades, has often said summarizing their life together, “there was never a dull moment.” Smith (1906-1996) was a highly original artist who possessed all his mental faculties and considerable physical strength to the end of his long and productive life. He was also known for strong opinions, especially about art and politics, and had a quick temper, regarding which, most friends and acquaintances agreed, it was best not to be on the receiving end.

Early formative influences on Leon Polk Smith’s character took place in legendary American circumstances. His family was among the nineteenth-century settlers in the West. His parents had arrived in present-day Oklahoma from Tennessee at the end of the great westward movement, probably after the Oklahoma land run of 1889, and had settled on land in what was still called Indian Territory. Smith was the eighth of nine children. Undoubtedly, in his youth he encountered many occasions at home in which he had to speak loudly and act quickly to defend his rights.

In 1907, a year after his birth, Indian Territory became part of the State of Oklahoma. It is difficult to imagine today the circumstances and atmosphere in which Smith passed his youth. It was a hardscrabble existence in which the whole family, young and old, worked the fields together for survival; inhabited homes that resembled shacks, at least at the start; and walked miles to go to school or just to fetch the simplest of life’s necessities. Life among the settlers was built on self-reliance, courage and conviction. This was a society in which, with enough determination, one could build a life quite unlike that of one’s immediate forebears. What could be more motivating than the promise of lives transformed, causing so many individuals to embark on transcontinental migrations of unknown length, dangers and hardships?

Early on, however, Smith knew that the agrarian life was not an option for him. By the age of six, he related, he had already decided to become a teacher. After high school he worked for a few years on various ranches in Oklahoma, and later he worked building roads and constructing telephone systems in Arizona. These were the years of the Great Depression, and he faithfully sent his parents money to help pay the homestead mortgage. But that was for naught. The family farm eventually was foreclosed. With this sad event behind him, Smith felt free to start on his path to become a teacher as he had promised himself, and he returned home to enroll at Oklahoma State College, now East Central University, in Ada.

One of the defining moments of Smith’s life occurred at this college when he discovered an art studio door ajar. Previously, he had never seen any art, at least not consciously. It drew him in like a powerful magnet, and he felt comfortable there. He knew on the spot that he would become an artist. By 1934, ten years after his graduation from high school, he had earned his B.A. in English.

Other turning points ensued. Early in his teaching career Smith fell very ill and was confined for weeks in bed. He could not walk and was informed that he had contracted polio. Local doctors said they could do nothing more for him, and it was recommended that he be taken to the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. The trip was saga-filled. The small plane, flying through a winter storm, was forced down into a field because of ice on its wings. Smith related how, strapped down and covered with blankets, he was moved by the beauty of the light striking the ice-laden branches as they were sweeping past the plane’s windows, knocking loudly against the craft as it landed and came to a halt. Caught in blizzard conditions, the plane had landed in the middle of the Iowa countryside far from any town. But the patient and the pilots were basically intact. After some time had passed and the stranded travelers, one still very ill, wondered what to do, one of the pilots heard a train whistle in the distance and set out toward the sound. He came upon a train stopped by the storm. And that train was being rescued by engines sent down the line to clear the tracks to free it. To the astonishment of the small band of travelers, the train was traveling eastward in the direction of Minnesota.

Smith was saved. However, his prognosis was declared to be hopeless by the Mayo staff practically upon his arrival. Before being sent home untreated, he rejected aloud staff predictions that he would not live more than a few months. He declared them wrong. Furthermore, he insisted, in one year’s time he would return again to the teaching post that this sickness had caused him to leave. He further predicted that he would drive himself to work in his own car like he had before. As it turned out, he made his predictions come true.

Perhaps the disease was a paralyzing virus acting similarly to polio, or maybe it was just the force of Smith’s astoundingly strong will that allowed him to overcome the disease. One year later to the very day, he struggled down the front stairs at a relative’s home, one step at a time, sitting as he went. Helped to his feet by a sister-in-law who took care of him during his recuperation, he got to his car on crutches. He drove to the college alone, shifting the gears with both hands but with enough leg strength to clutch and accelerate. There, he was greeted outside the building by his colleagues and students. A few months later he was well enough to resume work.

Eventually, Smith’s restless mind drew him to pursue graduate studies, and he settled on Columbia University’s famed Teachers College. It was recognized as the most important learning center of its kind in the search for new educational methodology. When he matriculated, Teachers College was the domain of the distinguished and widely influential resident professor John Dewey. In class a teacher, Ryah Ludins, introduced him to the geometric works of contemporary European artists, and with her he visited the Albert E. Gallatin Gallery of Living Art at New York University. Two paintings in the collection by the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) caught his eye like no others. Smith’s visual imagination was transformed. He was deeply inspired by Mondrian’s works, if not fully convinced by the philosophy behind them. A pragmatic American in his approach, Smith took what he wanted from the aesthetic experience and left the theorizing behind.

However, it would be another few years before the influence of De Stijl, the movement inspired by Mondrian’s art, clearly manifested itself in Smith’s work. Critic Arthur Danto, in his analysis of Smith’s absorption of Mondrian’s style, suggests that the way in which Smith comprehended space is attributable directly to his Southwestern background. Smith’s perceptions of artistic space led to a quest to make color and form one. This quest consisted of a series of intuitive decisions rather than the theoretical, ruminative creative process that preoccupied Mondrian and other members of the De Stijl group.

A year after earning his M.A. degree at Columbia and returning home to Oklahoma, Smith had earned enough to plan his first trip to Europe, in the summer of 1939. He visited the major countries of Western Europe with the exception of Germany and the states on its eastern borders, which were already closed to tourism because of the brewing political circumstances. Once back in Oklahoma, Smith decided that it was time for him to seek a post elsewhere on a more advanced level. He became an assistant professor of art at Georgia Teachers College in Collegeboro.

Smith prospered in Georgia and made influential friends on the faculty. While holding a full-time job, he pursued his art and was inspired by a trip to Mexico. Prophetically, his first one-artist show took place in New York at the Uptown Galleries in January and February 1941. The fifteen paintings and eighteen watercolors were figurative, and reviewers generally found them praiseworthy. In the following year two more exhibitions followed in rapid succession, and Smith’s reputation was growing. The first of these 1942 shows consisted largely of works inspired by Mexico, and it was also Smith’s first one-artist exhibition in a museum, taking place at the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences in Savannah. The second 1942 exhibition, however, was his debut in abstraction and took place at the Pinocoteca Gallery in New York. Also in the same year, Smith left Georgia when he felt that the state government’s resistance to campus desegregation was too far from his deeply held convictions. He accepted a post as State Supervisor of Art Education in Delaware, where much segregation remained in place but was less obvious. Smith worked against segregation throughout the state’s educational system by helping to integrate teachers’ organizations and their professional conventions.

Smith’s values can be traced in part to the example of his parents, who taught their children to lead a life of principled independence and respect for the rights of others. When he was still quite young, one of Smith’s brothers had married a woman of Chickasaw origin, who taught him her songs and language. His parents themselves had Cherokee ancestry. Although at the time Oklahoma had only a small African American population compared to its American Indian population, Smith’s parents were committed to the principle of equal opportunity and instilled this in their offspring. They had observed the marginalization of the American Indian population by the white settlers, and they encouraged their children to recognize their own Indian ancestry by socializing openly with all of their neighbors, regardless of origin. As a consequence, Smith would prove to be a staunch, early supporter of the civil rights movement during his first two full-time appointments outside Oklahoma.

Although he was pleased with his working situation and with the results of his efforts in Delaware, after two years Smith felt it was time to move on. “With me, New York City was love at first sight,” he wrote. The artist within him, it appeared, had gained from the experience of three consecutive summer-school sessions in New York, and he had grown rapidly in his professional art teaching posts.

He had a yearning for New York that had to be satisfied once and for all. In 1944, he determined to return. Lacking funds to remain financially independent, Smith sought a Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation fellowship. In the process of application, he was offered a job assisting at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later to become the Guggenheim Museum) by Hilla Rebay, who was director of both the foundation and the museum. She had informed him that he was too late for the current funding cycle but that he could apply the following spring.

It was an important learning opportunity, coming at the right moment for him, to work among examples of art by the leading European geometric abstractionists. As part of the Guggenheim Fellowship that Smith eventually received, he traveled back to the Southwest to proselytize as an art educator for the new abstraction, distributing Guggenheim materials in Oklahoma and New Mexico, where he still had many contacts. Santa Fe had a long-established, growing artists’ community, and he even attempted, unsuccessfully, to organize a show there of some of the Guggenheim’s collection.

Finally, at the beginning of 1945, Smith returned to New York City. He had arrived at his spiritual home at last. He immediately benefited from exposure to new ideas gained though contact with artists throughout the city sharing and exchanging information. Although he resisted joining any artists’ organizations, he remained in touch and counted numerous artists as friends, particularly Burgoyne Diller and Milton Avery among others. The unique scale and configurations of the city, its immense buildings and interspersed cavernous spaces, continually recalled to Smith the broad sweep of Southwestern landscapes of mountains, canyons, and plains. New York’s grid system of streets seemed to him the perfect urban setting.

Seen from its heights, the city symbolized in actual life all that the discovery of Mondrian’s works had meant to Leon Polk Smith in art. During the next few years Smith established affiliations with various galleries and maintained studio and living spaces in buildings housing other artists, while leaving on occasion for visiting teaching posts. An appointment lasting two years at Rollins College in Florida was followed by a brief residence in Cuba. In 1966, Smith established a summer home on Long Island at Shoreham, which for a time also served as his principal residence. For most of the remaining fifty years of his long creative life Smith remained in New York City.

Seen from its heights, the city symbolized in actual life all that the discovery of Mondrian’s works had meant to Leon Polk Smith in art. During the next few years Smith established affiliations with various galleries and maintained studio and living spaces in buildings housing other artists, while leaving on occasion for visiting teaching posts. An appointment lasting two years at Rollins College in Florida was followed by a brief residence in Cuba. In 1966, Smith established a summer home on Long Island at Shoreham, which for a time also served as his principal residence. For most of the remaining fifty years of his long creative life Smith remained in New York City.

From the publication for Leon Polk Smith American Original, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, The University of Oklahoma, 2006, pages 9-20