Leon Polk Smith Interview with and article by Addison Parks, Courtesy ARTS Magazine and Reprinted in Joan Washburn Gallery, Leon Polk Smith Paintings 1945-50 and Recent Paintings shows, September 22 – October 30,1982

Leon Polk Smith admits to being one of the twice born; art too claims its converts. Seated in his New York apartment, which also hosts his studio, he speaks softly and serenely of the life art has shared with him. The air is surprisingly fresh and relaxed, it doesn’t feel like New York. His living room is cool and bright from a crossfire of east and west exposures, high up they overlook Union Square on one side and face a cathedral of water towers on the other. Only Smith’s paintings dress the walls, and they light the room with an elegance which is betrayed only by their jaunty and jubilant spirit. He explains that while he is an ardent art enthusiast, all of his ideas come from his own works, and they serve him well by being where he can look at them. He speaks with a gently rhythmic but a touch crusty southwestern accent, and there is still a shadow of the rugged frontier about him, which can be traced back to his work.

“I discovered art my last year in college … 1934. Having grown up in Oklahoma and having been older than the state, there wasn’t much art there. So it was still younger than I at college age, and I had never seen an original painting. I don’t think I knew anyone very well who even had art in their vocabulary. And it’s quite by accident that I discovered art. That last year, I was in a building I had never been in before, walking down the hall, looking into the rooms as I passed. . . and this room had students and they were painting and drawing. And somehow that fascinated me immediately. I thought: I wish I could do that. And l went in and asked the instructor if I could come in and work for the rest of the term. He said yes.

I think I realized very quickly that I had always been an artist, and that that was what I wanted. That I would always keep it for myself, that I would never prostitute it, or do anything with it just for money.

I had prepared to be a teacher. When I started school, I said, I want to be a teacher, and it never entered my mind…. Even after I discovered art, and said I was going to be an artist, I knew that to make a living I would do what had been my first choice, which was teaching. I taught for about twenty-five years.

After I finished college, and taught one year, I came to New York in 1936 to study at Columbia … get my Masters … education and psychology. I knew I wasn’t going to start selling paintings (he laughs). Paintings didn’t start selling to somehow support me until about 1957. That’s when I stopped teaching.”

From the awesome horizontality of the Oklahoma plains to New York’s concrete peaks and valleys, Smith’s one preoccupation has been space. From the late thirties through the early fifties it was the Constructivist space of Mondrian which dominated his scope: pure rectilinear abstraction with a parity of positive and negative form. Like many others working under the mast of Constructivism, Smith was looking for the next step up, a stage further in the evolution. Some painters pursued lyrical abstraction, but these solutions sat too self-centered to excite him. So he pushed on.

Center Column Blue and White, 1946

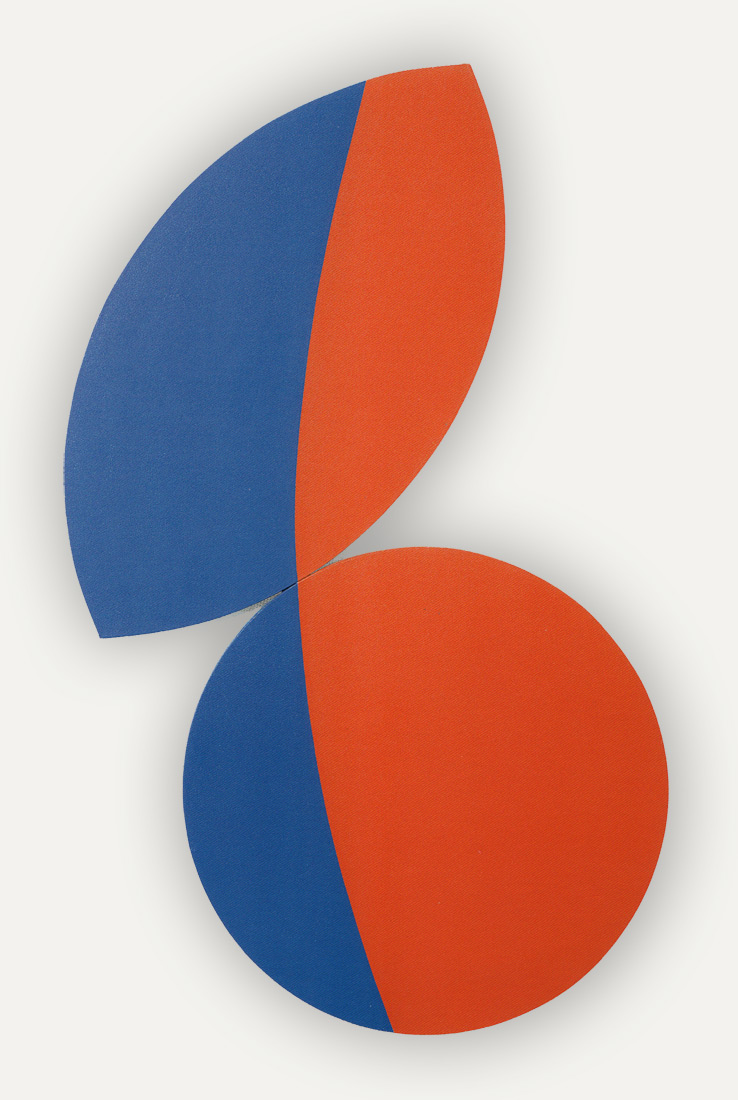

“When I discovered this thing in 1954, of dividing a canvas into two areas, painting in two colors, I did about twelve to fifteen tondos before I was able to carry the idea over into the rectangle. Because I discovered the idea on a circular format, you know I must have told you about seeing this athletic catalog … the illustrations that were done that were pencil drawings rather than photographs, of a baseball, tennis ball, football … that came into my studio, that was in the mail. I don’t know why it was sent to me … found myself going through the catalog … looking through the drawings. I certainly was not interested in any of them as a baseball or a basketball, but I was looking. And I thought, what the hell am I doing this for, why am I looking at this ? And a little voice says, because that’s what you’re looking for … that excited me and l knew immediately what it meant. I rushed into my studio, got some paper and a compass and started drawing circles and dividing them up. Then l had to start inventing my own break up. I was inspired. Because that presented what was I looking for?

“When Mondrian died, I think 1945, people said he had hit a dead end, or a stone wall and I said I don’t think so. There is no such thing as a stone wall except in one’s mind. I said to myself, I think it would be wonderful to use his great discovery of the interchange of elements of form and space, or background– foreground, although he only used it at a direct angle or a straight line–if one could find a way of using that in curvilinear form-and that’s what I was looking for, all through the forties …

“I certainly wouldn’t have gone to an athletic catalog to find it, but that’s where I found it. Of course the shapes and lines were very limited, and immediately had to start finding my own, which I did. But then that created a space there that I had never seen in painting before. It was flat and at the same time it was curved. It was like a sphere. The planes seemed to move in every direction, as space does. And so I thought, maybe that is because that’s on the tondo. I’ve got to find out if that is true or not. I’ve got to do some on a rectangle to see if the form and the space still moved in every direction. And it did. So it was exciting to do a painting on a rectangle that seemed to have a curved surface. It was the first time, you see that I had made an important step myself, or contribution in art.”

Color and shape are the converging planes which form the fulcrum over which Smith see-saws his space. They form the language of which he is a master. Color and shape are his domain; the crossbars of his scope; his words. With them he writes poetry; poems which magnificently sweep their time and space into a single gesture.

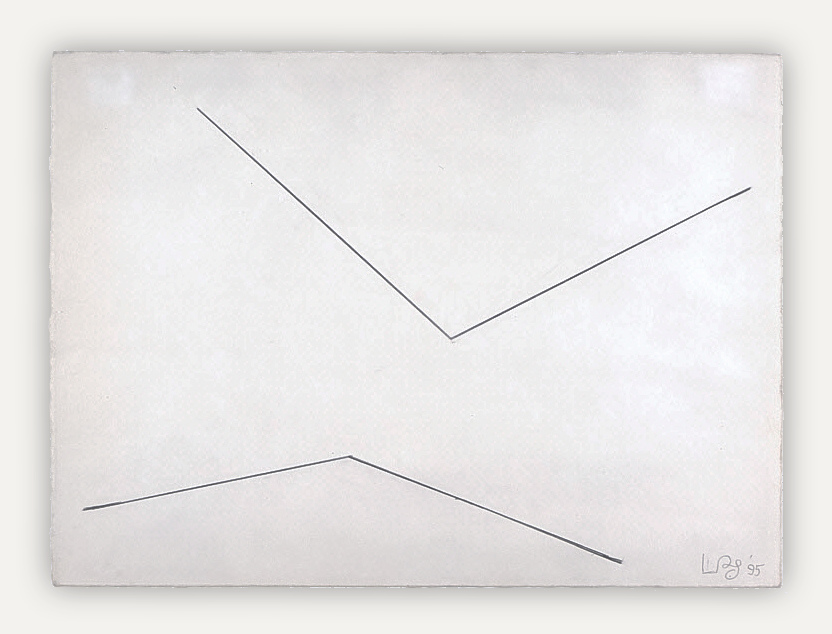

In space there is no up or down; up here is down there on the other side of the globe. Smith enlarged the concept of space in painting to meet with the twentieth century, everything moves at a diagonal. He first started experimenting with this in the rectilinear Constructivism of the forties; he implied lines which moved diagonally between points. Later he exposed the diagonals and still maintained a vocabulary of implied lines. Both are central to his dialogue, especially today.

New Moon For August, 1983

In the multiple panels Smith takes the concept of positive/negative parity one step further. He invites the surrounding space into the experience, and activates it into an equal exchange. The painting becomes a point of departure – a runway into space.

We sense the awe in this work, and wonder. These latest paintings are of a dimension so large, so fast and so deep, they tower like futurist space machines, seeming to pulsate on the threshold of infinity. Smith constantly talks of excitement as though it were an essential. He has a faith in what art can do, and be, and this is supremely evident in his work; so much so that with it he restores even our doubt in the doubt intrinsic to both.

“…lsn’t it simply wonderful to be able to paint? That’s what l wanted to do. Now I can – It’s something I would pay to do, if I were able to, if I had to.”

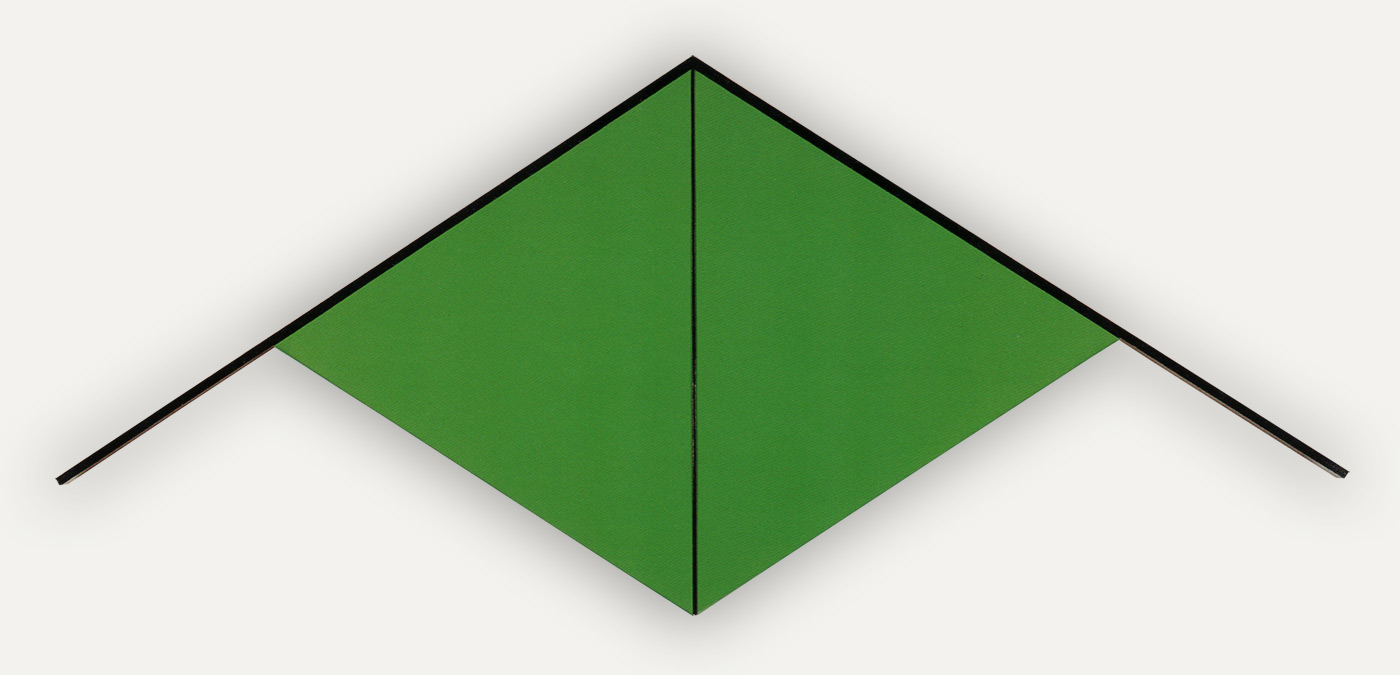

Green, Two Black Edges, 1984

There is a hard and fast line drawn in Leon Polk Smith’s work that has been there for over three and a half decades. It has been in his life forever. You could call it the broad hard-edged horizon spanning the Oklahoma plains where he was born and raised, or the rigid constructs of Mondrian’s radical planar abstractions which inspired Smith so profoundly in the Thirties.

Both of these are true, but more than anything else surely, that line is the strong and steady path of a wise and fiercely indomitable optimist. In Smith’s latest paintings the presence of that line is greater than ever, and with it comes the impact of something great, something that can be sensed.

Rori – Blue, Red, Blue, 1988

In these paintings Smith has introduced an element which has its roots in planar abstractions he has been doing since the early Fifties. It is that line, black and hard and fast. Not always as straight as it is now, but it has always been there; independent and yet unified, and also unifying. In these new paintings, however, its purpose has taken on a new dimension. Now it helps Smith do better something he has been doing since way before it became either an issue or a trend in painting: bring the surrounding wall into the picture and take the picture out into the surrounding wall. But this wouldn’t be the first time Smith has preceded a trend; Op. Minimalism, hard-edge, and monochrome were just a few to follow his lead. If Smith’s paintings are so breezy in spirit that the canvases float like kites in the sky and soar, and they do, then it is the line that brings them back to earth and reunites them with their environment.

Constellation No.5, 1972

The evolution of Smith’s own radical oeuvre began in the early Fifties with the tondo, the round canvas, a final departure away from Mondrian. Since then he has worked with regulated symmetrical shapes like folding screens, squares with rounded corners, and joined multiple canvases, always using unmodulated planes of color joined on a hard-edged seam. More recently he began using irregularly shaped canvases, placing them in tandem but not necessarily joined. The diagonal, as much a part of his oeuvre as the circle, played a critical part in carrying the viewer into the work and off into his space. These irregular shapes were very successful at turning the wall around the work into the work and then back out, so that the relationship became one of a figure-ground. This naturally meant that the wall would take shape with the work, thereby enlarging the sphere of the work’s activity.

Floating Black, 1984

In one of the very latest in that series, Smith uses a white plane in the picture to further the merging of canvas and wall. The blue shape skyrockets while the wall moves into the white plane and behind the blue. At the same time the white plane, ellipse-shaped, can work independently and press up against the blue and act like a color. It can even become the primary shape in the painting, making the blue fall away. It is interesting that color is something unfettered by any prejudice with Smith. Interesting but not surprising. For him all colors are beautiful, are good, are of equal value, are fresh.

Most recently it is the black line that assumes the burden of unification between the work and its environment. Smith has literally attached a wooden straight-edge, painted black, to the perimeter of his canvas frames to lock on along one or two sides and extend off the corners and out into the surrounding space. It reminds us of what he has always made clear through his work, that space is not just out there but all around us. If there is one thing that this work brings home, it is that we live in space and we can all realize that space. It is also interesting to note just how complementary this work is to not just space but people. Its color, scale, and shape are as human as they are modern.

If one looks at work Smith had done even forty years ago, it is still so fresh; yet looking at this recent work one is struck by how it brings us right up to the edge of time, our time. It may anticipate the future, but more than anything else it gives us that like-no-other feeling of facing the elements (destiny) on the bow of a great ship with the ocean (frontier) parting at our feet. It’s this-is-now, dammit, wake up! That’s great, and it doesn’t happen very often.

This work speaks magnificently for itself, so what am I running on about? Hell, I’m just trying to keep track of its wake. Still, more than anything else, more than its power to define our space and time, which is so tremendous it is sometimes hard to deal with, it is the poetry of color and shape in this work that makes it mean so much. They are probably one and the same thing, but each painting is like a new take on life, another all-things-being-equal way of saying keep on, because it is out there: Hope. This is the kind of sight(vision) that gives credence to art-as-celebration-of-life, which by now is sadly well shopworn. But I don’t forget it. The strong line in Leon Polk Smith’s work is life line.

untitled, 1995

Three Chosen Space Areas/Activated by Poetic Energy/LINE=Where Two Space Areas Converge

1995 Wall Drawing, The Brooklyn Museum